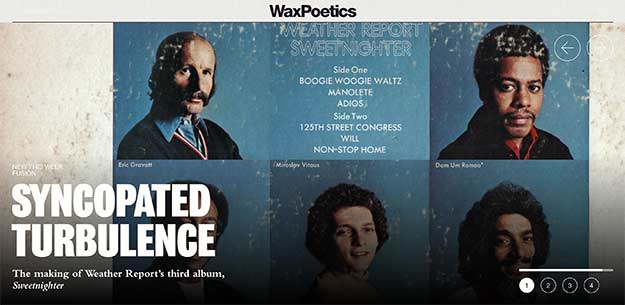

The good folks at Wax Poetics have an excerpt of my book Elegant People: A History of the Band Weather Report up on their website right now. You can view it here. The excerpt I chose deals with the making of Weather Report’s third album Sweetnighter. It was the beginning of the transition to Weather Report’s mature style, exemplified by the album’s two dominant tracks, “Boogie Woogie Waltz” and “125th Street Congress.” (The book chapter on Sweetnighter delves into many other aspects of that album as well as the changes that happened to the live band in the aftermath.)

It is appropriate that Wax Poetics host this excerpt. The editor Brian Digenti gave me my first opportunity to interview Joe Zawinul at his home in Malibu in 2003. That led to the publication of my article about Joe in Wax Poetics issue 9. This in turn planted the seeds for what eventually became my book many years later. If it hadn’t been for Brian, I don’t know that I would have pursued a book at all.

At its core, Wax Poetics is rooted in hip-hop, a music whose antecedents are the soul, jazz, funk, and disco of the sixties and seventies; hence, the nexus to Joe Zawinul and Weather Report. At least initially, hip-hop was constructed by sampling bits and pieces of old records—a horn stab, a drum beat, or a bassline—a measure here, a measure there. Once sampled, these fragments could then be looped and repeated, tempo- or pitch-shifted, and layered with other sounds likewise captured to build up an entirely new musical work.

Since records were the raw materials in this process, it was important to find the ones that contained the best material. This gave rise to the evocative term cratedigger, which describes someone who searches for rare vinyl in musty used record stores, garage sales, and flea markets. The true experts at the game develope an encyclopedic knowledge of the producers, labels, and musicians of yore, and when they find a good one, they collect anything he or she has done. As one prominent hip-hop producer noted, “If someone is great, I’ll follow everything they do. There’s no way they can hit something great one time and not do it again.” Weather Report, it turns out, was something great. Its records are documented to have shown up in 165 hip-hop titles as of this writing.

Joe had mixed feelings about this. On the one hand, he was all for making music this way. Regarding sampling, he told me, “Why not? Let people express themselves. These kinds of things are like an instrument. It’s like a language.” But he was opposed to the appropriation of his work without compensation. A 1992 Down Beat interview described Joe as “raging” as he complained about rappers “borrowing” portions of Weather Report tunes without permission. “If you steal something, steal it, and play it yourself. In the case of sampling, some type of money should be paid depending on what is being used,” he said.

Earlier that same year, he also addressed the topic in Music Technology magazine. “People do this [extract samples] on my music a lot. You know what I think about it? I think it’s good, but it’s only good if the original people (a) get credit for it, and (b) get paid for it. That’s only fair.” He cited one use of “125th Street Congress” in which the group’s management contacted him for permission, and the end result was that Joe and the group shared publishing, and he got credited on the record. “This is okay with me, it’s fine,” he said.

But in another example—a track by MC 900ft Jesus called “Truth Is Out of Style” that uses sixteen bars of “Cucumber Slumber” throughout—he complained, “They never contacted me. See, this to me is illegal. Herbie Hancock got me with this guy who is one of the greatest detectives of things like that. He got Herbie back $175,000 for one song. I mean, this is serious money being made. Some of these groups are getting No. 1 hit records using your ideas as a fundament.” (Listening to the track, you can see why Joe would be upset, as “Cucumber Slumber” provides the basis of the rhythm for the entire tune.)

Among the 165 samples of Weather Report tunes listed at whosampled.com are eight uses of “125th Street Congress.” This led Joe to boldly claim that he had invented the first hip-hop beat in 1973. An exaggeration? Of course! But that didn’t stop Joe from repeating the claim, including to me. You can read more about that in my book.