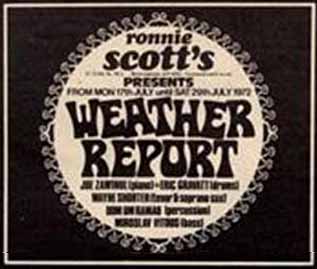

These gigs, which began on July 17 and concluded on the 30th, came on the heels of a busy month for Weather Report. Bob Devere, the band’s new manager, kept them on the road for most of June, 1972, with week-long stints at the Jazz Workshop in Boston, the Esquire Show Bar in Montreal, and the Lighthouse in Southern California’s Hermosa Beach.

Melody Maker dispatched its lead jazz writer, Richard Williams, to review the London performances. He also interviewed Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter, resulting in feature articles of both in the coming weeks.

Williams’s review reads as follows:

Weather Report is quite plainly one of the most effective bands of its type in the world. Where fusions are concerned, they operate seamlessly and effortlessly in the limbo between the electronics of rock and the creative improvisational interplay of jazz.

Their opening sets at Ronnie Scott’s Club, London, on Monday night obviously impressed the audience—indeed, who could fail to be moved in one way or another by the extreme facility, empathy, and power of this quintet?

They moved through sequences of highly sophisticated compositions with a practised ease which made it hard to define where writing left off and improvisation began, and there’s no doubt that they managed to create a far more spontaneous atmosphere than the Mahavishnu Orchestra or the Miles Davis groups, both of which seem rigid by comparison.

Individually, all five are masters. Joe Zawinul comes over as the leader, intentionally or not, playing with fuzz-tone and Echoplex to produce alien sonorities on the Fender piano. I do wish, sometimes, that he’d make use of the instrument’s softer tonalities—as he’s done on record in the past, to great effect.

As it was, his hard sound often blotted out the unassertive qualities of Wayne Shorter’s soprano sax—although when Shorter’s bitten-off phrases did cut through, the sound was marvelous. His tenor-playing is rather more aggressive, with a wholly personal tone and a method of phrasing which at first sounds crabbed but later reveals itself as astonishingly subtle.

Miroslav Vitous is a young giant of the bass, and it would have been good to hear more of him, too—particularly that incredibly emotional arco tone. Drummer Eric Gravatt impressed me much more than previously: he’s a neat, compact player who responds immediately to the musical needs of the other players, and who can also steam away at the head of the group when required.

Brazilian percussionist Dom Um Romão added a lot to the rhythmic and tonal palette, and seems much more group-conscious than his better-known contemporary, Airto Moreira. His playing is completely organic to the group’s overall sound, and his traditional melody on the berimbau, incorporating a little dance, was one of the highlights.

But still, I found that they left me a little cold for long stretches. Perhaps it’s the element of electronic sophistication which puts me off—or maybe Zawinul should just go easy on the volume pedal. Whatever, Weather Report have no peers in their ability to create extraordinary textures, and they should certainly be heard.

There are a number of interesting observations in this review. Regarding Zawinul’s “hard sound,” Joe was at the time using a harsh, distorted sound on his Fender Rhodes electric piano, as can be heard throughout the Live In Toyko album, recorded six months earlier. That would change with Weather Report’s next album Sweetnighter, and in the ensuing years Joe would produce among the most expressive bodies of work ever produced on the Rhodes electric piano.

Miroslav’s “arco tone” was a reference to his playing acoustic bass with a bow, something he did to beautiful effect on “Orange Lady” from Weather Report’s debut album. Coupled with Wayne’s soprano, it was a sound that Down Beat editor Dan Morgenstern described as “quite beyond description.”

As for Dom Um Romão, many reviewers of Weather Report’s shows singled out Romão for praise, even if they didn’t know what instruments he was playing. The berimbau, for instance, was an instrument that most American writers were unfamiliar with at the time. In addition to his musical sensibilities, Romão added some showmanship to the band’s performances, often walking though the audience while playing the berimbau.

Lastly, there’s Williams’s observation that Weather Report “left me cold for long stretches.” He wasn’t the only one to write something like that in 1972. Perhaps, as Williams suggests, it was those harsh—and loud!—Fender Rhodes tones that presumably led to ear fatigue among listeners after a while. But maybe there was more to it than that, because at the end of the year Zawinul would move Weather Report in a new and funkier direction.